Music that evokes images of royal ceremony, including Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary and Haydn’s Symphony No. 104. Pachelbel’s well-known Canon in D Major are followed by the Concerto for Harpsichord in G Minor. Handel completes the afternoon with Zadok the Priest, performed alongside the Syracuse University Oratorio Society.

PROGRAM

*NO INTERMISSION

Thanks to our sponsors for this performance!

PROGRAM NOTES

Let’s face it: the title of today’s concert—“Coronation Celebration”—is a bit hyperbolic. Still, there’s celebratory music, music written by a member of a royal family, one crowning achievement by a composer who was royally treated by his admirers, as well as music written for an actual coronation. So…

We open with music of celebration: two short pieces often brought out at weddings— although, curiously, neither was composed with marriage ceremonies in mind. In fact, the first seems a seriously inauspicious wedding-day choice, shrouded as it is in bad ...

Let’s face it: the title of today’s concert—“Coronation Celebration”—is a bit hyperbolic. Still, there’s celebratory music, music written by a member of a royal family, one crowning achievement by a composer who was royally treated by his admirers, as well as music written for an actual coronation. So…

We open with music of celebration: two short pieces often brought out at weddings— although, curiously, neither was composed with marriage ceremonies in mind. In fact, the first seems a seriously inauspicious wedding-day choice, shrouded as it is in bad luck and romantic tragedy. It’s not clear when Jeremiah Clarke (1674–1707) wrote his Trumpet Voluntary (originally titled “The Prince of Denmark’s March”)—or even what form it originally took (it may have started out as a harpsichord piece or a piece for trumpet and strings). But it is clear that it’s the only piece he wrote that’s remembered—and that until fairly recently, it had the ill-fortune to be credited to Henry Purcell. It’s doubly inauspicious as a wedding piece, because Clarke himself was never married, having killed himself because of thwarted romance. Need more? It gained popularity as a wedding march largely because it was used at the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana—hardly the model marriage. Still, it’s got the right wedding spirit, and you won’t find very many “Wedding Music” CDs or playlists that don’t include it. It’s been arranged and re-arranged innumerable times; today, we’ll hear an edition by R. L. Minter.

The Canon by Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706) is still more popular as wedding music. It’s another work that has somehow come to represent, for most of the public, a composer’s whole output—and even if you think you don’t know it, you’ll recognize it when you hear it. It achieved its fame slowly, though; for hundreds of years, it was virtually unknown, and when it first showed up on recordings, almost no one was impressed. Then two radically different versions, neither authentic, appeared in 1968. One was a highly romanticized version by conductor François Paillard, the other a rock arrangement by the group Aphrodite’s Child (co-founded by Vangelis, of Chariots of Fire fame). Add to that its use in the soundtrack of the award-winning film Ordinary People, and it was suddenly ubiquitous, heard in a staggering variety of arrangements and adaptations, by classical ensembles and popular music groups alike. It’s not clear how it got associated with weddings, but its service in that capacity seems enduring.

The Canon, despite its apparent simplicity, actually has a complex double structure. On one level, it is a chaconne (or passacaglia—the terms are generally used interchangeably), a series of variations set over a repeated bass. The form was used often in the Baroque period, but was also a favorite of later composers such as Brahms (the finale of the Fourth Symphony is a chaconne), Britten, and Shostakovich. On a second level, the variations are canonical. A canon is a musical form in which a melody is begun by one voice, echoed after a fixed period of time by the same melody in a second voice, and so on. (A round like “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” is the simplest form of canon.) Here, there are three voices (originally three solo violins, today the full violin section), staggered so that when the first violin starts playing Variation 2, the second violin is still in the middle of Variation 1, and the last is just starting out. It’s all extremely elaborate, especially as the variations get faster and more ornate. But it’s so finely crafted that you hardly notice its intricacy.

You’ve almost certainly heard the Pachelbel before. The odds are nearly as good that you haven’t heard our next work—and that, unless you are an intense devotee of Baroque music, you’ve never heard of its composer, at least until you read the publicity for this concert. Even today’s soloist, Bonnie Choi, a baroque expert and “a passionate advocate for women’s music,” was “very surprised” to learn about this piece, the Concerto in G Minor by Wilhelmine, Margräfin of Bayreuth (1709–1758). Wilhelmine was the eldest sister of Frederick the Great, and was apparently largely responsible for nourishing his interest in music. After she married the Margrave of Bayreuth, she spent much of her time as a patron on the arts. Nowadays, Bayreuth is best known as the home of the yearly Wagner Festival—but Wilhelmine was the person largely responsible for making it such an attractive place that Wagner chose to set it up there. She was not only a patron, however; she was also a composer, yet another in a surprisingly long list of musical royalty that weaves from King David to Henry VIII (and, of course, Frederick the Great) on to Beethoven’s sponsor Archduke Rudolf and further.

How good a composer was she? It’s hard to judge, since many of her compositions are lost. Fortunately, this Concerto is still extant (although it has not been easy for The Syracuse Orchestra to track down the parts)—and when you hear it, you’ll probably wonder why it’s never performed. Its most striking quality is its vitality, especially in its first movement (“Despite being composed in G minor,” Bonnie points out, “the piece is very energetic.”). And while its Bach influence is clear (“The beautiful melody of the 2nd movement,” Bonnie says, “reminds me a lot of Bach’s F minor Concerto”), so is its individuality (its “unique harmonic sequence sets it apart”). Wilhelmine’s Concerto is made more engaging still by “its extensive ‘solo harpsichord’ sections and the interplay between the harpsichord and the orchestra,” as well as by the substantial flute part, no doubt intended to be performed by her husband or brother.

There are cadenzas for the first two movements—on this occasion, Bonnie will use those written by her friend Ivan Bosnar, who’s on the organ faculty at Syracuse University. “The first uses a recitative style, adding a bit of dramatic flair.”

The premieres of the first three works on this afternoon’s concert were probably low-key events. The first performances of our two closers were not. The Symphony No. 104 in D (1795) by Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) was, in fact, the culmination of two massively successful trips to London—both organized by English impresario Peter Salomon—for which he had been invited to write a dozen new symphonies. Universally known as the “London Symphony,” it’s an imposing work in four movements, scored for what was a large orchestra at the time, and it shows Haydn at his peak, able to write music that’s both immediately audience-pleasing and formally ingenious. Typical of Haydn, it consistently throws us off balance—sometimes with its mixture of the majestic with the whimsical, sometimes with local jokes (like the surprising silence that interrupts the third movement minuet), sometimes with the way it builds the most imposing structures from materials that wouldn’t seem to have the potential for grandeur. The last movement, for instance, begins with a Croatian folk song that gets the kind of treatment usually reserved for major statements. Haydn probably didn’t think of this as his last symphony at the time—he was in good health (he lived for more than another decade), and some of his greatest music (including The Creation) was yet to come. But it certainly stands as an appropriate farewell to the genre.

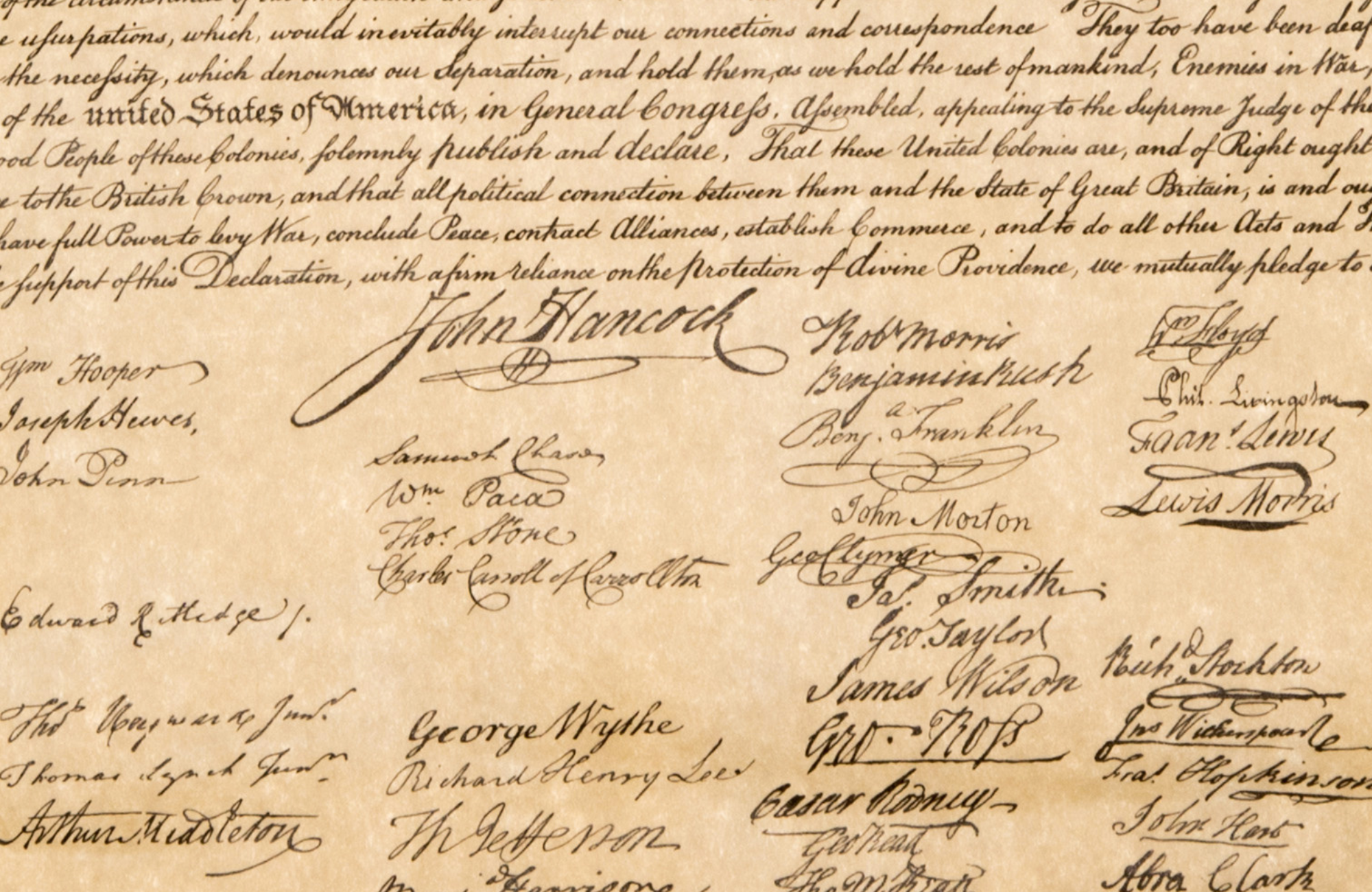

After the Haydn, our concert finally turns to actual coronation music: Zadok the Priest. With a text drawn from the first chapter of First Book of Kings, it was one of four anthems that George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) wrote for the coronation of King George II in 1727, and it has been, for reasons that will be clear when you hear it, repeated at every English coronation since then. It begins with an introduction of remarkable harmonic ingenuity, one that builds inevitably, with increasing tension, to the shattering arrival of chorus, drums, and trumpets. A relatively light middle section, in 3/4 time, gives us a chance to catch our breaths before the uplifting final section, to the text “God save the King, Long live the King, May the King live forever! Amen. Alleluja!”The words may make you think of the “Hallelujah Chorus” from Messiah, which Handel wrote a decade and a half later; the music will have a similar effect.

The first performance, in Westminster Abby, featured a much larger group that ours does (the orchestra had 160 players). But in the more restricted confines of St. Paul’s, we’re confident that we’ll make as grand a noise. We’re confident, too, that the performance will be better—by all reports, the premiere was a disaster.

Peter J. Rabinowitz

Have any comments or questions? Please write to me at prabinowitz@syracuseorchestra.org

FEATURED ARTISTS

Bonnie Choi is one of America’s most distinguished and versatile harpsichordists, who “displays dazzling technique and draws new colours from her instrument” (South China Morning Post), and who is known for her “wonderfully expressive playing” (Audio Technique). Her numerous honors include prizes received at the International Harpsichord Competition ...

Bonnie Choi is one of America’s most distinguished and versatile harpsichordists, who “displays dazzling technique and draws new colours from her instrument” (South China Morning Post), and who is known for her “wonderfully expressive playing” (Audio Technique). Her numerous honors include prizes received at the International Harpsichord Competition in Brugge, Belgium; the National Association of Young Performers Competition and a Finalist at the Pro Musicis Award Competition. She has concertized widely in North America and Asia. Her performances have been heard on public radio in the United States and Hong Kong, and she has recorded for VM Music.

Dr. Choi has given presentations in the United States at the MTNA national conferences and NCKP conferences on piano pedagogy; masterclasses and lectures in China on the piano. On the harpsichord, Dr. Choi has given lectures and master classes at the National Harpsichord Competition in Kansas, the Hanoi Conservatory of Music in Vietnam, the Shanghai Conservatory of Music in China, Baptist University and the Academy of Performing Arts in Hong Kong. She was a visiting faculty member at Shandong Normal University in China.

Dr. Choi teaches harpsichord and piano at Nazareth College and Syracuse University. She is the founder and harpsichordist of Air de Cour. Many of her piano students have won both state and local piano competitions.

John Raschella is currently Principal Trumpet with Symphoria. Prior to that for 30 years he was Principal Trumpet and Associate Principal trumpet of the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. He has performed as Co Principal trumpet with the Pittsburgh Symphony and has performed with the Philadelphia Orchestra along with the symphony orchestras ...

John Raschella is currently Principal Trumpet with Symphoria. Prior to that for 30 years he was Principal Trumpet and Associate Principal trumpet of the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. He has performed as Co Principal trumpet with the Pittsburgh Symphony and has performed with the Philadelphia Orchestra along with the symphony orchestras of Houston, Minnesota, Buffalo, Rochester and Jacksonville. He has also been a featured performer at the International Trumpet Guild Conference and has recorded with the Pittsburgh and Syracuse Symphony Orchestras. In the summers he has performed as principal trumpet of the Eastern Music Festival in N Carolina and the Spoleto festival in Italy as well as a frequent performer at the Skaneateles festival.

Mr. Raschella attended the Manhattan School of Music and the Curtis Institute of Music where he received an artist diploma. Mr. Raschella has taught at Ithaca College and is on the faculties of Hamilton College and Syracuse University. He has given master classes at The Curtis Institute, Ithaca College and Nazareth College.

Mr. Raschella is a native of Syracuse having grown up in Dewitt and remembers his first musical experience as going to a young persons concert at the war memorial and hearing the Syracuse Symphony at the age of 9. It changed his life and turned him on to classical music! His children are also musicians with daughter Mary (violin) a string teacher in the Williamsville school district and son David (french horn) who is attending the Juilliard school.

When not playing the trumpet you will find he and his wife Bonnie aboard their boat “BonGiovanni” where they love to cruise the Erie Canal and the great lakes!

Founded in 1975, the Syracuse University Oratorio Society is a large chorus comprised of Syracuse University students and community members that regularly performs choral-orchestral masterworks with the Syracuse Orchestra. The Oratorio Society is directed by Dr. Wendy Moy.

Founded in 1975, the Syracuse University Oratorio Society is a large chorus comprised of Syracuse University students and community members that regularly performs choral-orchestral masterworks with the Syracuse Orchestra. The Oratorio Society is directed by Dr. Wendy Moy.

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two ...

Described as bringing an “artisan storyteller’s sensitivity… shaping passages with clarity and power via beautifully sculpted dynamics… revealing orchestral character not seen or heard before” (Arts Knoxville) Lawrence Loh enjoys a dynamic career as a conductor of orchestras all over the world.

After an extensive two year search, Lawrence Loh was recently named Music Director of the Waco Symphony Orchestra beginning in the Spring of 2024. Since 2015, he has served as Music Director of The Syracuse Orchestra (formerly called Symphoria), the successor to the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. “The connection between the organization and its audience is one of the qualities that’s come to define Syracuse’s symphony as it wraps up its 10th season, a milestone that might have seemed impossible at the beginning,” (Syracuse.com) The Syracuse Orchestra and Lawrence Loh show that it is possible to create a “new, more sustainable artistic institution from the ground up.”

Appointed Assistant Conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony in 2005, Mr Loh was quickly promoted to Associate and Resident Conductor within the first three years of working with the PSO. Always a favorite among Pittsburgh audiences, Loh returns frequently to his adopted city to conduct the PSO in a variety of concerts. Mr. Loh previously served as Music Director of the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra, Music Director of the Northeastern Pennsylvania Philharmonic, Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of the Syracuse Opera, Music Director of the Pittsburgh Youth Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Associate Conductor of the Colorado Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Denver Young Artists Orchestra.

Mr. Loh’s recent guest conducting engagements include the San Francisco Symphony, Dallas Symphony, North Carolina Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Sarasota Orchestra, Florida Orchestra, Pensacola Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, National Symphony, Detroit Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Seattle Symphony, National Symphony (D.C.), Utah Symphony, Rochester Philharmonic, Indianapolis Symphony, Calgary Philharmonic, Buffalo Philharmonic, Albany Symphony and the Cathedral Choral Society at the Washington National Cathedral. His summer appearances include the festivals of Grant Park, Boston University Tanglewood Institute, Tanglewood with the Boston Pops, Chautauqua, Sun Valley, Shippensburg, Bravo Vail Valley, the Kinhaven Music School and the Performing Arts Institute (PA).

As a self-described “Star Wars geek” and film music enthusiast, Loh has conducted numerous sold-out John Williams and film music tribute concerts. Part of his appeal is his ability to serve as both host and conductor. “It is his enthusiasm for Williams’ music and the films for which it was written that is Loh’s great strength in this program. A fan’s enthusiasm drives his performances in broad strokes and details and fills his speaking to the audience with irresistible appeal. He used no cue cards. One felt he could speak at filibuster length on Williams’ music.” (Pittsburgh Tribune)

Mr Loh has assisted John Williams on multiple occasions and has worked with a wide range of pops artists from Chris Botti and Ann Hampton Callaway to Jason Alexander and Idina Menzel. As one of the most requested conductors for conducting Films in Concert, Loh has led Black Panther, Star Wars (Episodes 4-6), Jaws, Nightmare Before Christmas, Jurassic Park, Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz and Singin’ in the Rain, among other film productions.

Lawrence Loh received his Artist Diploma in Orchestral Conducting from Yale, his Masters in Choral Conducting from Indiana University and his Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Lawrence Loh was born in southern California of Korean parentage and raised in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He and his wife Jennifer have a son, Charlie, and a daughter, Hilary. Follow him on instagram @conductorlarryloh or Facebook at @lawrencelohconductor or visit his website, www.lawrenceloh.com